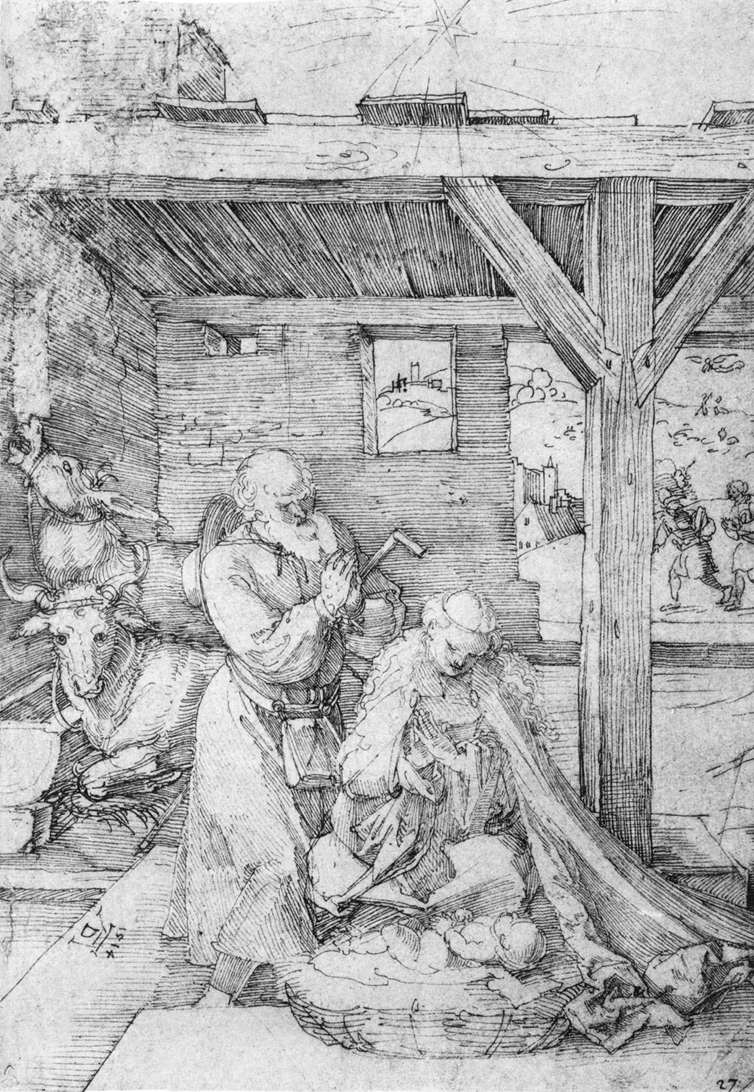

The Nativity, by Albrecht Durer (1514)

Christmas has many customs, varying from culture to culture. One of the most annoying of our own culture’s customs is the annual attack of Friendly Fire, in which sincere Christian brothers and sisters exercise their freedom of conscience and expression, informing the rest of us that we are submitting to Satan by celebrating the holiday. They expect to shock us by declaring a) that Jesus wasn’t born on December 25, b) that Christmas is really a heathen holiday, and c) that Christmas really isn’t that important anyway.

These three points are enough to spark hours and days of debate. But I’ll confine myself to the third point just now.

It’s true that Christmas is not the chief festival of the Christian calendar. That honor belongs to Easter, the feast of the resurrection. And our disproportionate cultural emphasis on Christmas over Easter is indeed a sign of wrong priorities. However, that argument means less now that our culture has been pretty thoroughly de-Christianized. The secular, commercialized celebrations of Christmas and Easter aren’t really matters of much theological importance.

But it’s wrong to suggest that Christmas is not an important celebration.

Christmas is the Festival of the Incarnation (that means that God, a Spirit, became flesh, a human being with a heartbeat, blood pressure, and an alimentary system). And the Incarnation (as Ron Burgundy would put it) is “kind of a big deal.”

I’ve talked about the Incarnation before here. I’m Incarnation-centric in my theology. For me, the Incarnation is the truth on which everything else pivots.

Culturally we still live in the wake of the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment was a philosophical movement that took its inspiration from Newtonian Science. The Enlightenment point of view was aptly expressed by Alexander Pope:

NATURE and Nature’s Laws lay hid in Night:

God said, “Let Newton be!” and all was light.

For the men of the Enlightenment, Newton’s discoveries were the great dividing line written across history. For them, all history was either “Before Newton” or “After Newton.” Before Newton, the world was mired in superstition and ignorance. After Newton, the wise began to understand how things really worked. In the future, they were sure, all questions would be answered; the closed system of the universe would be mapped, down to the smallest square inch.

In the time since the Enlightenment, those expectations have been stymied. To modern people, science is no longer a savior, but a monster. The great crusade now is to legislate ourselves back to an imagined pastoral golden age, where ugly, carbon-spewing, Newtonian engines will no longer poison the earth.

Part of the problem is the whole Enlightenment doctrine that Newton was the Avatar of Truth. In fact that watershed in history did not come with Newton, but back where the Church located it, at the birth of Christ. At the Incarnation.

It was the Incarnation that presented the most radical new idea in history – that matter and spirit were not incompatible. That matter was not (as most of the old pagans believed) something low and contemptible, but an honorable creation of God, worthy of a wise man’s study. That’s how science began, in the laboratories of Christian monks.

Maybe we could solve part of our present problem if we turned our gaze back to the Incarnation. Maybe meditating on the birth of Christ might help us to create a friendlier science, one more harmonious with the nature that God declared “good” at creation.

A Chestertonian meditation to help us prepare for Christmastide.