Now and then, ideas converge for me, which is about the best fun I have in life. And then I feel compelled to write about them here, in the sight of my guardian angel and everybody, inviting public scorn and ignominy (I believe Ignominy is a town in Wisconsin. Good fishing, they tell me).

A while back I posted about what seemed like a breakthrough in my own mental life – by way of, of all things, a dream. I found a “place” in my brain where I could take shelter from intrusive memories. I even had an idea where that “place” was located – on the right side of the brain, just above the ear. The technique of resorting to this “place” has not proved the panacea I hoped at first, but it remains a useful trick for me in regulating my thoughts, and I still use it pretty much every day.

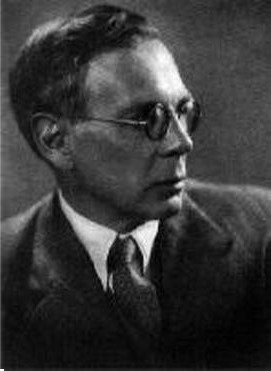

More recently, I discovered the psychiatrist Iaian McGilchrist, initially through the conversation with Eric Metaxas embedded above. I have not yet shelled out for any of his books, because they’re kind of pricey, but I’ve watched several more videos. So far as I can grasp his thesis, I understand it thus:

We all know that the normal human brain is bilateral. Most of my life I’ve been informed that the left brain (which controls the right side of the body) is the plodding, logical, workhorse of the mind. Meanwhile, the right brain is creative and spontaneous. Back in the sixties and seventies, the hippies were always trying to access their right brains.

McGilchrist’s thesis does not contradict these distinctions, but refines them. The left brain, he says, evolved for the purpose of concentration and task completion. It learns routines, devises systems, puts things in boxes and labels them. It’s what allows us to do things automatically. Its functions are necessary to our survival. But it considers itself very smart – smarter than it is. Its true purpose is to be the servant or “emissary” of the “master” – the right brain.

The right brain is where our real intelligence lies. The right brain makes imaginative leaps. It maintains a global awareness of its surroundings. It is creative and inventive. It’s meant to be in control.

All my life, the left brain has been associated with people like me – the orthodox, the conventional. Left brain people reduce everything to set formulas and are quick to judge. Which – I can’t deny – is not far from a description of my own nature.

But McGilchrist also directs his spotlight onto other kinds of idealogues – the leftists and fascists and communists and feminists and environmentalists, etc., etc. who’ve infested our politics and history for so many decades. They’re left-brain people too, he says, and we’re beginning to get tired of them (or so he hopes).

But here’s the point of tonight’s essay. In a recent McGilchrist video I watched, he made a comment that rang a little bell for me – he said, in so many words, “The left brain is, in fact, mad.”

I immediately recalled something G. K. Chesteron wrote in Orthodoxy:

If you argue with a madman, it is extremely probable that you will get the worst of it; for in many ways his mind moves all the quicker for not being delayed by things that go with good judgment. He is not hampered by a sense of humour or by clarity, or by the dumb certainties of experience. He is the more logical for losing certain sane affections. Indeed, the common phrase for insanity is in this respect a misleading one. The madman is not the man who has lost his reason. The madman is the man who has lost everything except his reason.

McGilchrist is not a Christian. By his own account, he values Christianity but is unable to believe in the miracle of the Resurrection.

Yet he has managed, after a century, to catch up to Chesterton, by the empirical rather than by the theological road.

Chesterton, I imagine, was thinking with his right brain.