It is a childish game I have always played and have never been able to resist—a game of arranging life, whenever possible, in a series of scenes that make perfect first-act or third-act curtains.

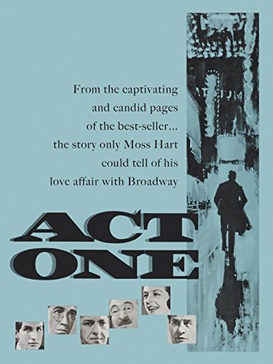

Wikipedia’s biographical article on Moss Hart, author of the autobiography, Act One, includes what seems to me a very telling detail. In the book, Hart describes his relationship with his aunt Kate, an eccentric semi-delusional who fancied herself a grand dame. She shamelessly sponged off her family, dressed in an affected “fashionable” style assembled from other people’s cast-offs, and was devoted to her nephew Moss. It was she who introduced him to the theater (cheap seats, of course), and who nurtured his fascination with that world. In the book, Hart tells how Aunt Kate died, tragically, while his first produced play was in rehearsals. She never knew of it, because he’d saved it as a surprise.

In actual fact, according to Wikipedia, Aunt Kate lived on for some time, becoming increasingly eccentric. Finally she turned on her nephew, breaking in on his play rehearsals and wrecking scenery. Once she set a fire backstage.

Now that I’ve finished Act One, it seems clear why Hart “edited” this scene of his life. The whole book is a lesson in storytelling. The truth spoiled the mood of the act, so he fixed it, as a good playwright does.

Moss Hart was born into an impoverished Jewish family in New York City (not apparently a religious family – they celebrate Christmas and he speaks occasionally of his love for lobster). His immigrant grandfather had come from a prosperous English family, but broke with them and emigrated. When his profession (cigar making) fell to automation, he was left without a living, a severe humiliation. Young Moss was the child on whom he lavished his attention. After his death, Aunt Kate took his place.

Thanks to Aunt Kate, Moss knew he wanted to be part of the theater, a ticket out of the poverty he hated, though he wasn’t sure what he’d do in the business. He tried, and abandoned, acting. Eventually he and a friend took jobs as social directors at a Jewish “summer camp,” an established cultural tradition in those days. These jobs were mostly about arranging entertainment, and Moss learned a lot, eventually becoming the best paid social director in the old “Borscht Belt.” But then he came up with an idea for his first comedy. Without his knowledge, a friend sent the play to the Broadway producer Sam Harris, who amazed him by calling him to ask if he’d mind collaborating with George S. Kaufman to bring the play up to professional standards.

George S. Kaufman was like a god to Hart. The rest of the book is a journey through the writing and production process for that single play. They “fixed it,” and tried it out in Atlantic City. The audience liked the first act, but it went downhill from there. Convinced they still have a salvageable show, the pair plunge into re-write after re-write, as out-of-town audiences continue to fail to find it funny. Then Kaufman gives up. Hart despairs. And then he has an inspiration and persuades Kaufman to give it one last re-write before the New York opening in four days. Then the big payoff.

Act One is a brilliant drama, disguised as an autobiography. I’m not sure how much to trust it in terms of facts, in light of the Aunt Kate episode, but the mechanics of storytelling are exemplified beat for beat, and they work wonderfully. Act One is a fascinating, amusing, bittersweet and ultimately triumphant personal story. It’s a masterful short course in plotting for a writer in any discipline.

Highly recommended.