A new form of religious community appeared for the first time in history: not a nation celebrating its patriotic cult, but a voluntary group, in which social, racial and national distinctions were transcended, men and women coming together just as individuals, before their god.

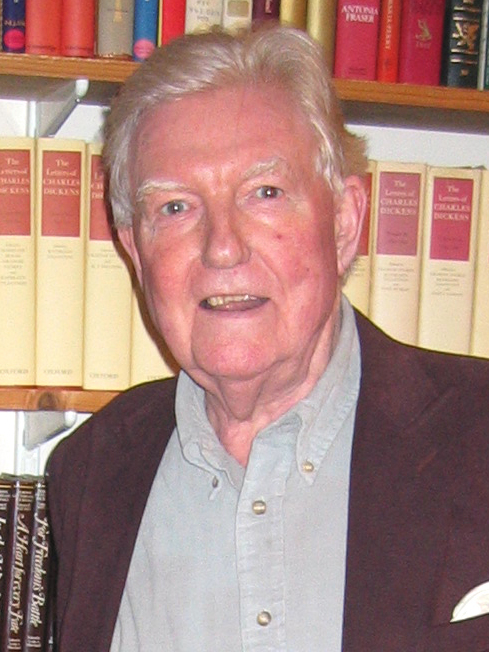

It’s done at last. I have successfully worked my way through the Marathon length of Paul Johnson’s A History of Christianity. And I have to tell you from the start, it wasn’t what I expected or hoped for. The late author, of whom I’m a big fan, started out (like many thinkers on the right) on the left, and gradually worked his way to conservatism. This book was an early work, published in 1975 when he was (I assume) still in transition. And conservative politics doesn’t necessarily entail Christian faith – I don’t know what Johnson believed. This book didn’t give much clue.

Also, the book is somewhat misnamed. It’s not a history of Christianity, but of western Christianity. Once Rome breaks with Constantinople, the Eastern Church (as well as all the smaller eastern groups) drops off the stage except for when they interact with the West.

He starts well, arguing that it’s silly to question whether Jesus actually existed. Even better, he seems fairly sure that we have a fair idea what He taught. But his description of the formation of the canon and of orthodox doctrine is thoroughgoingly naturalistic. By this account, the scriptures were assembled through chance and politics out of a selection of wildly variant alternate manuscripts (I’m pretty sure this is not true). And the fights over doctrine were wholly political, decided in the end by brute power. The author’s greatest admiration seems to be reserved for certain heretics and the marginally orthodox – Arian, Pelagius, Erasmus. “Sensible” Christians who concentrated on good works rather than abstract doctrine and faith.

Then follows the long, sad chronicle of how the persecuted church (not so much persecuted most of the time, he insists) gradually rose to imperial power in Rome, and organized – on a model invented by St. Augustine – a unitary civilization in which Church and State were one thing. And corruption inevitably set in. The system gradually broke down, leading in time to the Reformation and the Enlightenment, and to the decline and challenges of the modern world.

It’s a depressing read, to be honest. Which is not to say I didn’t learn valuable stuff. I was particularly interested in the account of the decline of papal power in the 12th Century. It helped illuminate my reading of Norwegian history and the way King Sverre was able to ignore a ban and excommunication (as his contemporary King John did in England).

He ends in the “present” (1975), expressing optimism that the ecumenical movement can lead to a more flexible, dynamic church in the world (and we all know how well that’s worked out).

The oddest part, for this reader, was the author’s epilogue, in which he explains that he actually does consider Christianity a force for good in the world:

The notions of political and economic freedom both spring from the workings of the Christian conscience as a historical force; and it is thus no accident that all the implantations of freedom throughout the world have ultimately a Christian origin.

My big problem with A History of Christianity is that it takes him 516 pages to get around to mentioning that. The impression the reader gets from plowing through his long catalog of persecutions, heresy trials, witch hunts and religious wars must certainly be that Christianity has been a greater force for suffering and evil than Nazism and Communism combined. And I’d wager most readers have quit before they get to that epilogue.

Near the beginning he tells an anecdote about Bishop Stubbs, professor at Oxford, who, when he met a young historian, noticed he was carrying a book of which he disapproved, and said to himself, “If I can hinder, he shall not read that book.” He emphasizes the importance of not being like Stubbs, of listening to all ideas and making up one’s own mind.

That’s a noble sentiment, and I approve as a reader. But as a Christian concerned with souls, I would have to say, “Keep A History of Christianity out of the hands of young and impressionable Christians. If they’re looking at all for reasons to walk away from the faith, they’ll find plenty of them here.”