Benjamin had found the work on a square-rigger hard and testing beyond anything he had imagined. Nevertheless, as the barque turned away from the gale to run fast to the south, not slogging into the eye of the wind or hove to, but for the first time truly sailing, he became aware of something else: fascination, and the rapture of a young man in glamorous jeopardy.

Among the many things I didn’t know before I read Derek Lundy’s The Way of a Ship was that, at the very end of the Age of Sail, during the late 19th Century, there was a time when the square-riggers served their own nemesis. It was apparent to all that the steamship was on its way to replacing wind-sailing ships. But those steamships needed coal to run on, and (for technical reasons having to do with engine efficiency and payload) at the time the cheapest way to transport coal was in sailing ships. So the sailors carried the fuel for their usurpers. These last sailing ships were not wooden, but iron, their rigging made of steel. The profit margin in this commerce was narrow, so the companies economized by keeping the crew sizes at a minimum. The food stores were minimal as well. Men died because of it, but that’s one of the costs of doing business.

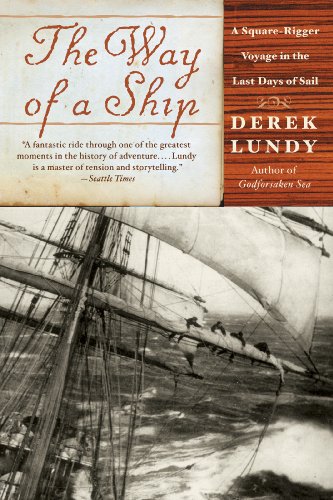

Author Derek Lundy conceived an interest in a collateral ancestor of his, a young Irishman named Benjamin Lundy who sailed in a coal ship around the Horn in 1885. He hunted for information, and found it sparse. The old logs, and most of the old letters, had disappeared. The best he could do was learn what he could about the commerce in general, and then imagine a voyage for his ancestor, on a fictional ship, The Beara Head, with an imaginary captain and a (mostly) imaginary crew, and send them through a fairly typical voyage from Liverpool to Valparaiso, and then on to San Francisco.

It’s a harrowing journey. The book it most recalled to me was Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast. But Dana dwelt less on the horrors of the voyage (fewer sailors die in his book). Author Lundy did some sailing as part of his research, including time on a genuine square-rigger. Also he’s a superior wordsmith. Thus he’s able to convey some inkling of the kind of dangers and sufferings these sailors experienced. The oddest thing about it, when you think of it, was that all this was routine. People took it for granted. If you went through an adventure like this today, you’d be on television and get book deals. It’s as if we’re a whole different species from these men.

I found The Way of a Ship utterly engrossing and educational. I recommend it highly. The rare political asides seem pretty even-handed. Some profanity, which kind of goes with the territory.