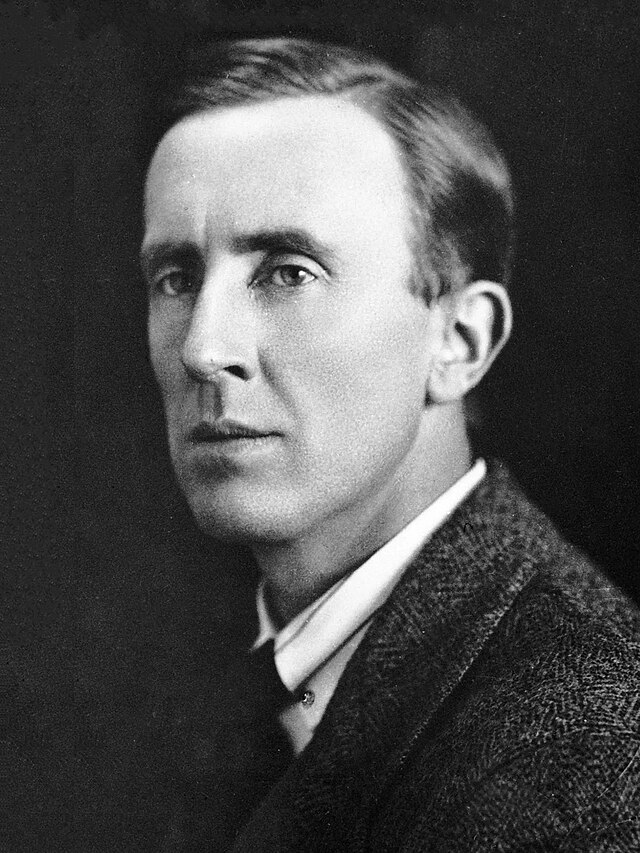

I’m still working my way through The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. It’s quite a long book (though not nearly as long as the 3 volumes of C. S. Lewis’ letters. But this collection makes no claim to being complete).

In any case, the business takes time. So I hope you’ll forgive my giving the book my “reading report” treatment. I suspect there’s enough interest in Tolkien’s work among our readers to warrant multiple posts.

What may strain your tolerance more is my selection of passages from the letters that I relate to my own writing. I’m keenly aware that, even standing on the shoulders of authors like Tolkien and Lewis, I’m shorter than they are. But as I obsess my way through the final stages of producing The Baldur Game, I snatch at any straw of reassurance I can find – or imagine I find.

Anyway, here’s a nice one, from a September 30, 1955 letter to a reader (friend?) named Hugh Brogan. Brogan had written with a criticism of the archaic prose style Tolkien used in The Two Towers. The professor never actually sent this letter, but dispatched a note instead, saying “it would be too long to debate.” But he kept the letter in his files.

He agrees with Brogan’s rejection of what they called “tushery” – the use of archaic words in literature to give an impression of antiquity – words like “tush,” “forsooth,” and “eftsoons.” Victorian writers liked to toss such morsels into their dialogue, but they’re now considered an affectation.

However, Tolkien insists that he does not employ tushery:

But a real archaic English is far more terse than modern; also many of the things said could not be said in our slack and often frivolous idiom.

I jumped at this, because it relates to my own style (in my Viking books). I actually avoid archaic words, unless I can find no modern equivalent. (I’d love to use the word “leif” as an adjective, meaning “to wish to”, for instance. But I don’t think I ever have, because nobody knows the word anymore.)

I’ve actually chosen to simplify my word choices to achieve an antique effect in these books. The general modern writer’s rule, “Don’t use a Latin word when an Anglo-Saxon word will do,” is taken to an extreme. Rather than use a word derived from Latin or French, I’ll sometimes even invent a compound word (in the German fashion) made out of two simple English ones.

In addition, I make use of my knowledge of Norwegian. Norwegian sentences are often constructed differently from the English. I discovered that when I re-cast a sentence in Norwegian word order, I get an effect that “feels” like Old Norse.

I like to think it works. The most satisfying praise I ever got for my writing was back in the 1990s, when a reader told me he looked up from Erling’s Word and was surprised to find himself in the 20th Century.