I’m still slogging through a Very Long Book (a good book, but comprehensive), so tonight I’ll report on another tale from The Complete Sagas of Icelanders. This is the last story in Volume I, which means I’ll be coming to longer sagas again in the next one. I’m not sure what I’ll do to vamp while I’m reading future long books.

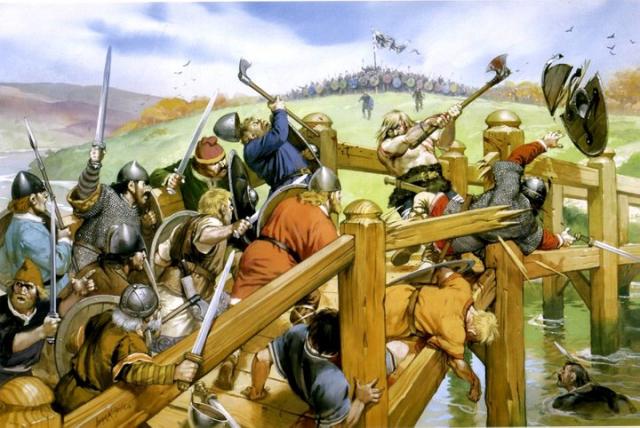

To my delight, this tale turned out have considerable personal interest. It involves Erling Skjalgsson’s grandson, Eystein Orre (son of Erling’s daughter Ragnhild and Thorberg Arnesson – you may remember the story of Thorberg’s courtship from King of Rogaland). Eystein had a sister named Thora who would, in time, become concubine (or wife, sources differ) to King Harald Hardrada, and would die with him following a legendary charge at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in England.

Our tale is the Tale of Thorvard Crow’s-Beak. Thorvard is a wealthy Icelandic merchant. He sails to Norway where he speaks to King Harald, inviting him to come down to his ship and accept the gift of a sail. (According to this article from the Viking Herald, the manufacture of one sail for a Viking ship could take as long as fifty years [!] Perhaps they mean 50 years in man-hours).

I’ve mentioned previously that King Harald appears uncharacteristically genial in most of these saga tales. But in this one we see him in his usual temper. He tells Thorvard, curtly, that he got an Icelandic sail once before, and it tore apart under wind pressure. So he’s not interested in another such gift.

However, Thorvard then offers the sail to Eystein Orre, the king’s best friend, and Eystein, on examining it, recognizes it as an excellent specimen. He accepts it with thanks and invites Thorvard to stop and see him at his own home when he sails back to Iceland. When Thorvard does so, Eystein gives him generous gifts.

And to cap it we are told that, on a later occasion, Eystein’s ship outsails the king’s. And when the king asks where he got this fine sail, Eystein tells him it’s one he had turned down. A nice final note for the storyteller – it could even be true.

I was surprised to see “Eystein Orre” translated as “Eystein Grouse” here. Orre does mean grouse, even in modern Norwegian, but I’m sure I read somewhere that Eystein got his nickname from Orre farm in Jaeder. Perhaps that’s the meaning of the farm’s name. If Eystein lived there, it would likely have been due to inheritance from Erling.

The Tale of Thorvard Crow’s-beak is one of the more plausible stories in the collection, just trivial enough to believe.