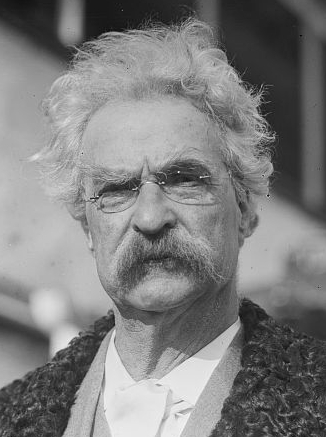

Mark Twain. Photo: Library of Congress

For example, he [William Godwin] was opposed to marriage. He was not aware that his preachings from this text were but theory and wind; he supposed he was in earnest in imploring people to live together without marrying, until Shelley furnished him a working model of his scheme and a practical example to analyze, but applying the principle in his own family; the matter took a different and surprising aspect then.

A few days back I posted a link to an article on the shameful domestic behavior of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. One of our commenters, “Habakkuk 21,” pointed me to Mark Twain’s essay, In Defence of Harriet Shelley. I downloaded it for my Kindle, and it made interesting reading.

As I’ve said before, I have ambivalent feelings about Mark Twain. I yield to no one in my admiration for his gifts as a novelist and humorist. He was one of the greats, and he’s given me plenty of good laughs. I like him less as a man, and when he gets on his Skeptical hobbyhorse he irritates me. On top of that, many of my generation saw Hal Holbrook (at least on TV) doing his Mark Twain show, in which he cherrypicked Twain’s writings to give the impression that he was essentially a man of the ’70s—the 1970s—born before his time.

But in In Defence of Harriet Shelley we see another Mark Twain—the Victorian middle class gentleman, the devoted husband and father, for whom nothing could be more vile than a man who abandoned his family. I expected a little more wit in this essay than is actually to be found here. The primary tone is withering scorn. It appears that Twain had little intention of entertaining the reader in this piece. He was morally outraged, and it’s the outrage that comes through.

I like Mark Twain a little better as a man, after reading A Defence of Harriet Shelley. It’s hardly a classic of Twain’s work, but it’s kind of nice having him as an ally for a change.