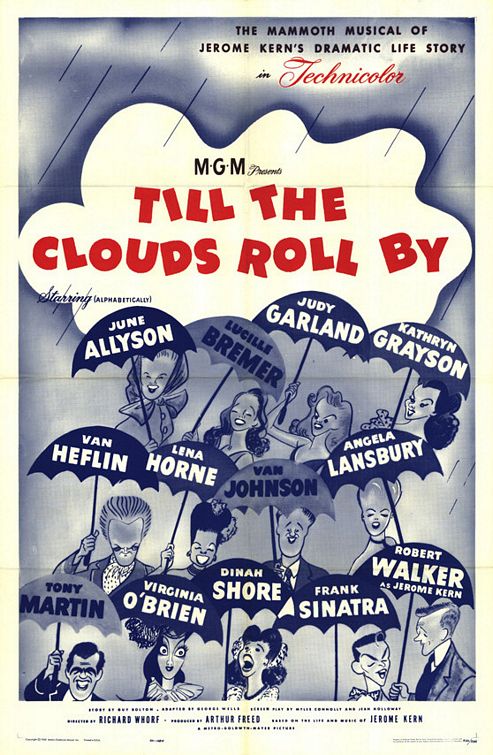

I caught an old movie the other day. “Till the Clouds Roll By,” starring Robert Walker (no relation). It’s a biographical film, based on the life of Broadway composer Jerome Kern.

I like old movies in general, but this one interested me because I knew Kern wrote along with P. G. Wodehouse and Guy Bolton in his early years, doing a lot to invent the American musical comedy as we know it. Up until their time, Broadway musical plays had been mostly adaptations of European ones. This team, plus a few others, invented more character-centric stories, where the songs always advanced the plot. I wondered how the movie would treat that collaboration.

They treated it, in typical Hollywood fashion, by replacing it entirely. In the movie, instead of working with various collaborators, the young Kern teams up with a fictional older lyricist named Jim Hessler (Van Heflin). The Hessler character comes fully equipped with a fictional family, including a young daughter who becomes a surrogate little sister to Kern, and adds dramatic conflict to the third act so that all can be resolved in the big musical climax.

That got me thinking about the subject of fictional characters. That is, fictional characters included in real life stories, in order to avoid using real people – who sometimes sue you (or their heirs do) if they don’t like the way they’ve been depicted. (Movies were made about Wyatt Earp before his widow died, but they had to change his name, because she refused to give approval.)

Perhaps the most famous case is Shakespeare’s Sir John Falstaff, introduced in Henry V, Part 1. Falstaff was a stand-in for a genuine historical figure named Sir John Oldcastle. Oldcastle had a similar career to the fat man in the play, except that he joined the Lollards, the proto-Protestant followers of Wycliffe, and eventually died a martyr’s death, roasted over a fire. His descendants, who were influential, made it very clear that they did not want their ancestor belittled, so Will Shakespeare just wrote Oldcastle out, replacing him with Falstaff. Probably just as well.

In both versions of “Shadowlands,” the film about C.S. Lewis’s marriage to Joy Davidman (I prefer the original BBC version), we see Jack together with his friends, the Inklings, debating, laughing, smoking pipes, and drinking beer. Except for his brother Warnie, who plays a major role in the play, all these friends are fictional. There is no J. R. R. Tolkien there, nor any Hugo Dyson or Owen Barfield. Including them (especially Tolkien) would have been a distraction, I imagine. The audience would be trying to identify them rather than following the story.

And they all had living families, always potential complications.

It makes perfect prudential sense to fictionalize.

And yet I always feel a little cheated when it’s done.