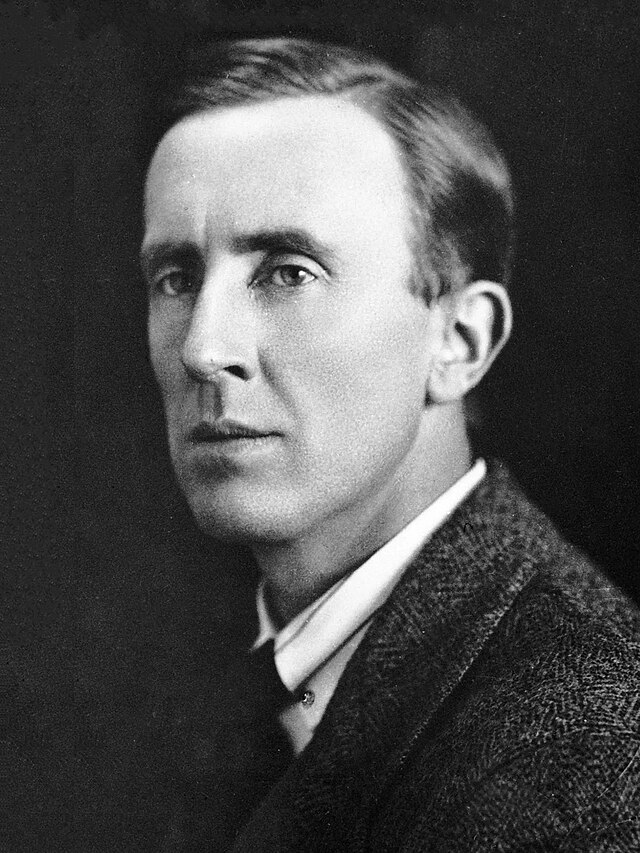

And it’s happy Friday to you again, dear Brandywinians. I hope my repeated posts about The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien this week haven’t bored you – I know Tolkien himself isn’t boring, but my own penchant for finding parallels to my work might easily have become tedious.

As an antidote, I’ll just finish the week out with a few choice quotations from some of the letters:

In reference to a pair of reviews of The Hobbit by C. S. Lewis, published in 1937:

Also I must respect his opinion, as I believed him to be the best living critic until he turned his attention to me, and no degree of friendship would make him say what he does not mean: he is the most uncompromisingly honest man I have met….

From the same letter:

The presence (even if only on the borders) of the terrible is, I believe, what gives this imagined world its verisimilitude. A safe fairyland is untrue to all worlds.

From 1941:

Nearly all marriages, even happy ones, are mistakes in the sense that almost certainly (in a more perfect world, or even with a little more care in this very imperfect one) both partners might have found more suitable mates. But the ‘real soul-mate’ is the one you are actually married to.

1943:

Anyway the proper study of Man is anything but Man; and the most improper job of any man, even saints (who at any rate were at least unwilling to take it on), is bossing other men.

1944:

I should have hated the Roman Empire in its day (as I do), and remained a patriotic Roman citizen, while preferring a free Gaul and seeing good in Carthaginians.

1944:

The future is impenetrable especially to the wise; for what is really important is always hid from contemporaries, and the seeds of what is to be are quietly germinating in the dark in some forgotten corner….

1944:

…Christian joy which produces tears because it is qualitatively so like sorrow, because it comes from those places where Joy and Sorrow are at one, reconciled, as selfishness and altruism are lost in Love.

I think these will do for tonight. Have a blessed weekend!