More Viking stuff tonight.

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Stamford Bridge, traditionally (though somewhat arbitrarily) reckoned as the end of the Viking Age. It happened near a village not far from York, in the year 1066. King Harald Hardrada of Norway, who was getting on in years, had made a pact with Toste, the estranged brother of King Harald Godwinsson of England, to conquer the country. Harald believed he had a technical right to the throne as legal heir to his nephew, who’d had a slim claim.

According to the saga, Harald brought a fleet of 300 ships from Norway. On September 20 they defeated an English army at Fulford, and then accepted the submission of Northumberland. They were on their way to receive hostages on the 25th when they were suddenly attacked by the army of King Harold Godwinsson, who had made a forced march from the south.

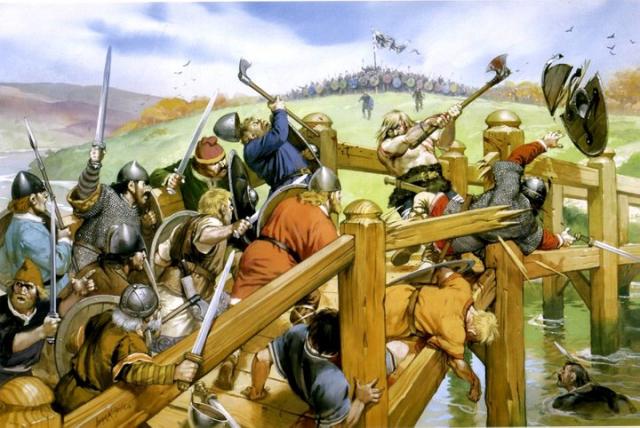

The English must have been exhausted, while the Norwegians would have been relatively fresh. However, the Norse were not prepared for battle and many had left their mail shirts behind, because the day was warm and they expected no trouble. The battle, by all accounts, was nevertheless a hard-fought one.

An interesting detail is a story found in English sources (but not, surprisingly, in Norwegian ones as far as I know) about a warrior who defended the bridge with an axe all alone for an extended period of time, giving the Norwegians time to form up their ranks. He was killed at last by a spear thrust from below.

According to the saga, the Norwegians might have won if King Harald Hardrada had not taken an arrow in the throat, finishing on English soil a military career that had stretched from Norway to Russia to the deserts of the Middle East. But that’s how saga writers tell stories – I wouldn’t be surprised if the truth was more complicated. In any case, it’s undisputable that Harald was killed there.

One final item, often overlooked, might be of interest to our readers. There was a final (third) stage of the battle, after Harald’s death, remembered in Norway as Orri’s Storm. A young man named Eystein Orri, who was betrothed to the king’s daughter, had been left at Riccall to guard the ships. When he learned of the army’s peril, he and his force set off at a dead run to join the battle. There was really little they could do for the cause except die with their king, and that’s what they did. According to the saga, they were wearing their mail. But the weight and the heat exhausted them so that they were nearly played out when they got to the battlefield. But then (if you can believe the saga), they went into such a berserk frenzy that they threw off their mail shirts and fought unarmored. This made them easy targets (some, according to the saga, died from sheer exhaustion).

Eystein Orri was Erling Skjalgsson’s grandson, through his daughter Ragnhild.

According to the sagas, of the 300 ships that sailed to England with Harald, only 24 returned home. The English said that whitening bones could still be seen on the battle ground 50 years later.